The essence of Indian philosophy is a luminous confluence of wisdom, spirituality, and humanism—one that transcends the constraints of time and geography. Anchored in the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita, and the teachings of revered sages, it envisions a cosmos where the individual self (Atman) awakens to its unity with the Supreme (Brahman). Its ultimate pursuit is not mere material triumph but liberation (Moksha)—the transcendence of ignorance, ego, and suffering through self-realization.

At its core resonates Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam—”The world is one family”—a principle that urges humanity to dismantle divisions and embrace universal kinship. It upholds Dharma (righteous duty), Karma (action imbued with responsibility), and Ahimsa (non-violence) as the fundamental tenets of existence. Unlike rigid dogma, Indian thought thrives on inquiry, reason, and adaptability, fostering an integrated vision of life that harmonizes mind, body, and soul.

Its message is one of equilibrium—between material and spiritual aspirations, self and society, individual progress and collective well-being. It envisions a world where knowledge flows freely, power is tempered with wisdom, and progress is measured not by wealth alone but by harmony and ethical integrity. In an age clouded by uncertainty, Indian philosophy remains a timeless beacon, urging humanity to seek truth, live with righteousness, and unite as a singular civilization.

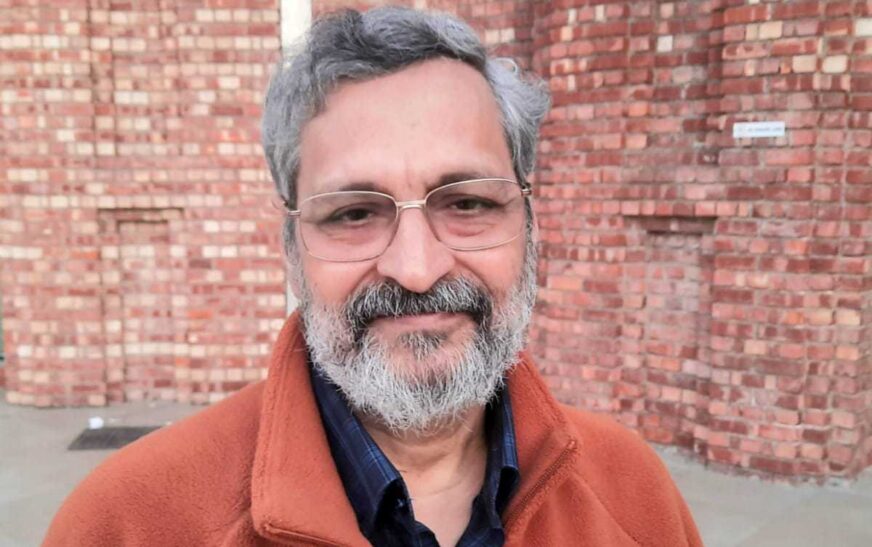

In an exclusive conversation with The Interview World, Dr. Manindra Nath Thakur, Associate Professor at the Centre for Political Studies, School of Social Sciences, JNU, shares his profound reflections on the essence of Indian philosophy and its deviations in contemporary times. He illuminates the transient conflicts within inclusive ideologies, underscores the imminent convergence of multilateral thought, and offers a thoughtful message for students delving into the depths of Indian philosophy. Here are the key takeaways from his compelling insights.

Q: How does the Sanatani ideology propagated by this regime align with true Indian philosophy, and what deviations have you observed over time?

A: Indian philosophy is an expansive quest for knowledge, deeply rooted in human existence and its expression across various traditions. When reduced to mere identity politics—whether in the form of Sanatani thought or any other ideological construct—it loses its essence. The core of Indian philosophy is not confined to any single language, sect, or tradition. Instead, it unfolds as a vast intellectual landscape where diverse cultures have engaged in profound dialogue, giving birth to a multiplicity of philosophical perspectives.

Consider the India of the 6th century BCE. Within a mere ten-kilometer radius of Vaishali, three towering philosophical minds—Mahavir Jain, Gautama Buddha, and Ajit Keshkambal—coexisted, each shaping distinct yet interconnected schools of thought. Vaishali, a thriving democratic society at the time, was a crucible of intense philosophical debate. Out of these debates emerged the doctrine of Anekantavada, the philosophy of multiple perspectives, which Mahatma Gandhi later embraced, calling himself an Anekantvadi.

This spirit of dialogue defines the Indian philosophical tradition. When the Greeks arrived, they exchanged wisdom with us, and we with them. The same intellectual reciprocity unfolded when Islamic scholars engaged with Indian thinkers, creating a synthesis of ideas that enriched both traditions. This ceaseless exchange of knowledge—this openness to learning and evolving—is the very essence of what it means to be Sanatani.

India stands apart as a land where nature itself has bestowed an unparalleled diversity—of languages, cultures, philosophies, and ecosystems. It is not merely a geographical entity; it is a living testament to the power of coexistence, synthesis, and perpetual intellectual inquiry.

Q: Given the current deviations from true inclusiveness, when can we expect acceptance of diverse sects, religions, and knowledge systems? Is meaningful inclusion possible soon?

A: India has always navigated the delicate balance between conflict and inclusion. History bears witness to this interplay. Consider the era of Dara Shikoh—a time when cultural synthesis thrived despite centuries of ideological and religious differences. Inclusion was not merely an abstract ideal; it was an ongoing process, unfolding even in the face of deep-rooted divides.

Over time, these differences must inevitably give way to a broader unity. Society itself is not inherently fractured. Temporary influences may sway people, but the deeper fabric of collective existence remains intact. Take Punjab, for instance. Many assume that Punjab’s militancy was quelled by force, but the reality is far more profound. A student of mine, who completed his PhD on this subject, uncovered an overlooked truth—Punjab’s syncretic traditions played a crucial role in preserving unity. Despite the currents of divisive politics, people remained bound by shared cultural expressions, as seen in the rise of collective music and other unifying forces.

This phenomenon is not unique to India. Across Asia, unity often emerges from the grassroots, defying imposed divisions. History reveals a striking pattern—whenever societies fracture under the weight of conflict, a simultaneous movement toward cohesion begins. The deeper forces of cultural and philosophical synthesis work tirelessly, ensuring that fragmentation never has the final word.

Q: How do you view the convergence of multilateral thought processes, given that politicians globally employ similar divisive tactics?

A: This phase is temporary. It does not signify a true cultural division but rather the management of a capitalist crisis. Wealth is concentrating in the hands of a few, and to sustain this imbalance, deliberate distractions must be manufactured. Look closely at the parallel between rising divisive politics and the accumulation of capital—they advance in tandem. This is no coincidence; the two are deeply intertwined.

Trump’s era makes this dynamic glaringly evident. As figures like Elon Musk amass unprecedented wealth, political polarization intensifies. The correlation is unmistakable. Yet, such politics, rooted in manipulation and diversion, cannot sustain itself indefinitely. I believe that people will begin to reclaim their unity.

Paradoxically, this period of division has also opened an unexpected avenue—one of renewed dialogue. For the first time in four decades, I see ordinary people actively engaging with perspectives beyond their own. They are questioning differences, reading each other’s texts, and exploring unfamiliar traditions. Hindus are studying Islam with curiosity, and Muslims are delving into Hindu philosophy. This intellectual cross-pollination is unprecedented since 1947, when a post-partition silence settled over these discussions.

Now, that silence is breaking. This moment, despite its turmoil, may well give rise to a deeper and more meaningful dialogue—one that has the potential to redefine how we understand and engage with each other.

Q: What message do you have for students studying Indian philosophy? How should they interpret these concepts in light of your narrative and contemporary developments?

A: Indian philosophy, across all six schools, begins with a fundamental question: What is its purpose? The answer is clear—it seeks to alleviate human suffering. It identifies three forms of affliction: Daihik (physical suffering), Daivik (existential and divine suffering), and Bhautik (material suffering). Collectively, these are known as Taap—the crises that burden human existence.

Philosophy, therefore, is not a mere intellectual pursuit. It is a path to liberation. Its purpose is to free human beings from these afflictions and guide them toward a higher state of being. To understand Indian philosophy, one must view it through this lens—not as an abstract discourse, but as a profound commitment to universal human emancipation.