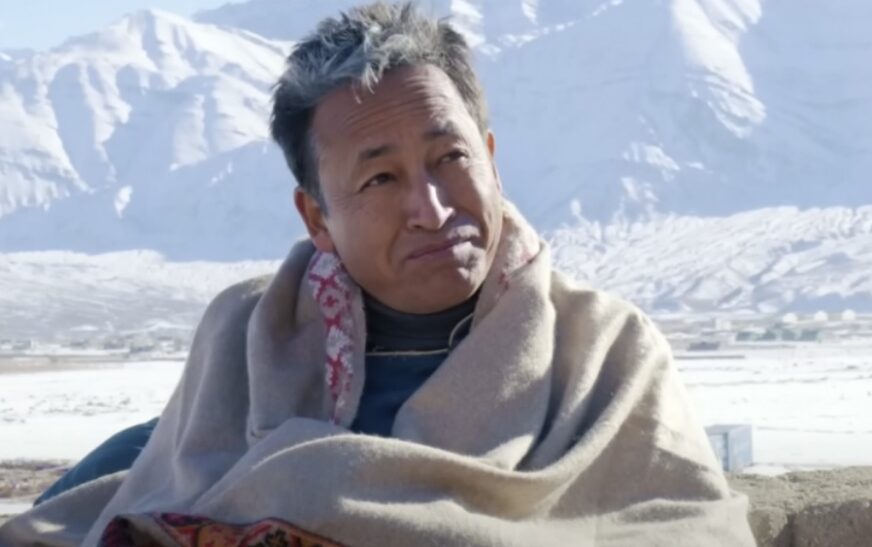

Sonam Wangchuk is a visionary engineer, innovator, and education reformist hailing from the remote Ladakh region of India. Wangchuk’s life journey has been a testament to his unwavering commitment to leveraging technology for social change, particularly in the realm of education.

Wangchuk gained international recognition for his pioneering work in sustainable development, particularly his innovative approach to addressing water scarcity in the arid landscapes of Ladakh. His most acclaimed project, the Ice Stupa Artificial Glacier, ingeniously harnesses the power of nature to store water in the form of ice stupas, which melt gradually to provide water during the crucial agricultural months. This innovation earned him the prestigious Rolex Award for Enterprise in 2016, catapulting him onto the global stage as a beacon of sustainable development.

Beyond his groundbreaking engineering feats, Wangchuk is a pioneer in educational reforms in the region. He founded the Students’ Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) in 1988, aiming to reform the region’s failing education system. Under his leadership, SECMOL developed innovative teaching methods tailored to the unique needs and challenges of Ladakhi students, emphasizing practical, hands-on learning over rote memorization.

In addition to his work with SECMOL, Wangchuk steers various initiatives aimed at promoting sustainable development, entrepreneurship, and environmental conservation in the Himalayan region. He continues to inspire and empower communities through his TED Talks, lectures, and workshops, advocating for a holistic approach to development that prioritizes environmental stewardship, social equity, and cultural preservation.

Sonam Wangchuk’s unwavering dedication to innovation, education, and sustainable development has earned him numerous accolades, including the Ramon Magsaysay Award, often referred to as Asia’s Nobel Prize, in 2018. His legacy serves as a testament to the transformative power of grassroots activism and the boundless potential of human ingenuity in addressing the most pressing challenges of our time.

In a special interaction with The Interview World, Sonam Wangchuk sheds light on his recent 21-day Climate Fast. This fast underscores the call for Ladakh’s statehood, the implementation of the 6th Schedule of the Indian Constitution to safeguard tribal rights, and the preservation of the region’s ecosystem. Let’s delve into the main points from his interview.

Q: What is the current status and condition of Ladakh as of today?

A: Global warming is relentlessly melting glaciers in the Himalayan region, including the pristine landscapes of Ladakh. This environmental shift, accompanied by erratic weather patterns, is exacerbating the frequency and intensity of natural disasters. Flash floods, landslides, and droughts have become all too common, wreaking havoc on the lives of inhabitants in the sparsely populated villages nestled within the mountainous terrain.

In light of these challenges, we must need urgent measures to safeguard the Himalayan region, particularly Ladakh, from further degradation. The rampant exploitation of natural resources, exemplified by mining activities, has already inflicted irreparable damage in neighboring regions like Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, and Sikkim. Now, Ladakh stands at a critical juncture, facing the looming threat of similar environmental devastation.

We must take proactive steps to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change and prevent the indiscriminate exploitation of Ladakh’s fragile ecosystems. Only through concerted efforts can we hope to preserve the natural beauty and ecological balance of this unique region for generations to come.

Q: What is the significance of the 6th Schedule demand, and how does it relate to the Climate Fast unto death?

A: In the rugged terrain of Ladakh, a relentless effort is underway to preserve the majestic mountains that define the region’s landscape. We must employ every available tool and provision to safeguard these natural wonders. However, Ladakh stands apart due to its predominantly indigenous tribal communities, comprising a staggering 97% of the population. In recognition of their unique cultural and societal fabric, the Indian constitution enshrines special protections for such regions under the 6th Schedule of Article 244.

This constitutional provision empowers the inhabitants of regions like Ladakh to chart their course of development autonomously, free from external interference. It is a testament to the recognition of the distinct needs and aspirations of indigenous communities, allowing them to preserve their way of life while progressing on their terms.

The journey towards securing Ladakh’s status as a Union Territory spanned seven decades, culminating in its realization in 2019. Yet, unlike the safeguards provided under Article 370, which previously granted a degree of autonomy, the current framework lacks specific provisions tailored to the unique challenges faced by hilly regions like Ladakh. This is where the significance of the 6th Schedule becomes paramount.

The 6th Schedule delineates a framework that grants indigenous tribes substantial autonomy over their affairs. Central to this framework are the Autonomous District Councils (ADCs), endowed with legislative and judicial powers. These councils wield authority over critical domains such as land, forest, water, agriculture, health, sanitation, and mining. It is a comprehensive mechanism designed to empower local communities to manage their resources and shape their destiny.

The optimism surrounding Ladakh’s newfound status as a Union Territory was further buoyed by assurances from the government regarding its protection under the 6th Schedule. This commitment was not merely rhetorical but was underscored by tangible pledges made by union ministers during official gatherings. Minutes of the SC/ST commission documented these assurances, solidifying the government’s stance.

Furthermore, the ruling party’s manifestos unequivocally prioritized the implementation of 6th Schedule safeguards for Ladakh. This commitment resonated with the electorate, as evidenced by resounding victories in successive elections. The mandate was clear – Ladakh’s protection under the 6th Schedule was not only a promise but a fundamental expectation.

However, the landscape shifted unexpectedly, and the government began to backtrack on its commitments. This turn of events has left the people of Ladakh grappling with uncertainty and disillusionment. In the face of this regression, there is a growing imperative to assert our rights and demand the fulfillment of the promised safeguards.

In conclusion, Ladakh’s quest for autonomy and preservation stands at a critical juncture. The promise of the 6th Schedule holds the key to securing the region’s future while honoring its rich cultural heritage. It is imperative that the government upholds its commitments and safeguards the aspirations of Ladakh’s indigenous communities.

Q: What role does the 6th Schedule play in Ladakh’s socio-political and ecological landscape?

A: As an environmentalist, I hold deep concerns for the delicate ecosystem of the high Himalayas, characterized by its glaciers and diverse flora and fauna. Ladakh, renowned as the 3rd pole of our planet due to its glacier system, plays a vital role in sustaining approximately 2 billion people, either directly or indirectly. Among them, one billion reside on the Indian subcontinent, constituting a quarter of the global population.

Introducing mining industries in these regions would not only inflict hardship upon the local inhabitants but also lead to severe water scarcity across the northern plains of India. Therefore, it is imperative to safeguard these vulnerable areas as sacred water zones. Preserving them is paramount.

For the locals, protecting their region, customs, culture, and land is of utmost importance, all of which are enshrined in the 6th Schedule of our Constitution, devised by our forefathers 75 years ago.

One of the remarkable aspects of our Indian Constitution is its embrace and protection of diversity, exemplified by the 6th Schedule. The world looks up to us for such provisions, and reneging on our commitments poses a significant problem.

This issue extends beyond my concerns as an environmentalist or the interests of the people of Ladakh—it’s a matter of national trust and ethics. When a party makes written promises during elections, they must honor them. Failing to do so is akin to issuing a bounced cheque and disregarding the consequences.

The outcome of the promise made to Ladakh will set a precedent for future elections across India. It will determine whether leaders can casually disregard their pledges or if the electorate will hold them accountable. Ladakh’s struggle serves as a crucial test case: either the government fulfills its promise after facing public resistance, or it becomes a cautionary tale for future leaders.

Ultimately, this issue revolves around ethics. Future leaders must learn from this experience, understanding the gravity of their promises and the necessity of fulfilling them.

Q: What are the concerns regarding the preservation of Ladakhi culture, and what potential impacts do you anticipate further development may have on the region?

A: If Ladakh is left unprotected, mining companies will arrive, as we often hear they are already surveying the mountains and valleys. Soon, major hotel chains will follow suit, attracting thousands of visitors. The delicate desert ecology of Ladakh, unlike urban areas such as Delhi, Lucknow, or Chennai, cannot sustain such influx. People here rely on just 5 liters of water daily, not the extravagant 150 liters in cities.

If 200,000 people, each consuming 150 liters of water, flock to Ladakh, the region will face a severe water crisis, spoiling it for both locals and newcomers. Every drop of water here is precious. Ladakh’s infrastructure cannot accommodate large crowds; even tourism has already caused significant disruptions. Now, consider the impact of a permanent large population influx. It would displace locals, turning them into refugees, and the newcomers would also suffer. This is the fear: the degradation of our land and culture, finely tuned over millennia to thrive in these mountains. Dilution of our heritage would render it unsustainable.