Gautam R. Desiraju and Deekhit Bhattacharya, in their book Delimitation and States Reorganization: For a Better Democracy in Bharat, present a powerful argument for redrawing India’s political map to restore balance and equity in representation. They contend that the decades-long freeze on delimitation has severely distorted the country’s democratic framework, concentrating political power, weakening governance efficiency, and skewing economic resource distribution.

Through meticulous research, the authors dissect the historical and political motivations behind this freeze—tracing its origins to the Emergency era and exposing how successive governments have extended it for political expediency. They make a compelling case that India’s current system of representation has entrenched an imbalance, favouring some states while marginalizing others, undermining the very essence of federalism.

A key insight from the book is the undeniable link between political representation and economic fairness. The authors argue that India’s existing federal structure disproportionately benefits states with larger representation, sidelining those with fewer seats in Parliament. They advocate for a periodic reorganization of states, alongside delimitation, to create a more proportionate and functional democratic system. Addressing concerns about national unity and administrative complexity, they demonstrate how smaller, more evenly sized states can enhance governance efficiency, promote economic specialization, and strengthen political stability.

To achieve this transformation, the book calls for a transparent, institutionalized framework to implement delimitation and state reorganization—one that aligns with Bharat’s civilizational ethos while addressing modern political and economic challenges.

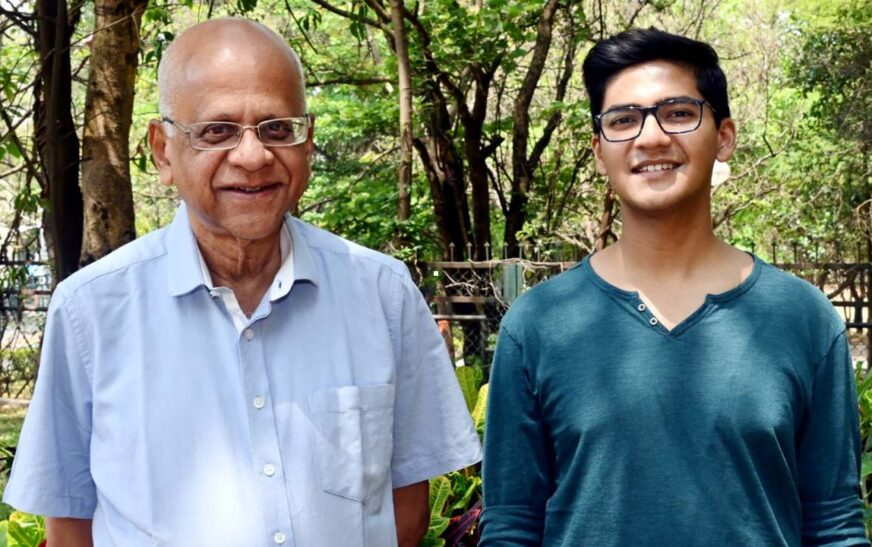

In an exclusive conversation with The Interview World, Desiraju and Bhattacharya dissect India’s current delimitation freeze and its far-reaching consequences. They explain how disparities in state sizes and representation distort federalism, governance, and economic policymaking at the central level. They highlight why smaller, more balanced states drive economic growth and administrative effectiveness. Most critically, they outline the necessary safeguards to ensure a fair, transparent, and politically neutral delimitation process. Finally, they lay out actionable policy steps to build momentum for this urgent reform, shaping a more just and efficient democratic future for Bharat.

Here are the key takeaways from their thought-provoking discussion.

Q: Your book argues that India’s current delimitation freeze has created a fundamental imbalance in representation. What were the main factors behind this freeze, and why has it persisted for so long despite its obvious drawbacks?

A: The delimitation freeze stemmed from the Emergency—an era when informed policymaking and domestic political discourse were effectively suspended. While the stated rationale was to promote family planning, the real motivation was Congress’ electoral calculus. At the time, nascent political movements in northern India were not just challenging Congress as a party but also resisting the ideological framework it had imposed on the nation.

In effect, the delimitation freeze was constitutional gerrymandering. By artificially deflating the value of votes in the northern states, it sought to neutralize emerging political forces—forces that eventually gave rise to the BJP and regional parties that displaced Congress. The Vajpayee government later extended the freeze, largely due to its fragile coalition, which forced it to carefully choose its battles.

Today, reversing this freeze aligns with the electoral interests of all major players. More importantly, it prioritizes national interest, ensuring a fairer representation of India’s evolving political landscape.

Q: How does the current imbalance in state sizes and representation impact federalism, governance, and economic decision-making at the central level?

A: The number of Lok Sabha seats a state holds largely determines its influence within the Union. Larger states like Uttar Pradesh wield immense political clout, often emerging as kingmakers in national politics. This outsized influence extends beyond elections, shaping the state’s bargaining power with the Centre. As a result, tax devolution, grants-in-aid, and financial allocations frequently follow electoral logic rather than objective need.

This dynamic severely distorts the principles that should guide India’s quasi-federal structure. It entrenches extractive state governments, incentivizes misallocation of resources, and undermines national growth. The stark disparity in representation—ranging from a single seat for Sikkim to a towering 80 for Uttar Pradesh—further skews governance priorities, creating systemic imbalances that ripple across the country.

Q: You mention that states like Goa and Bihar are treated differently by the Union. Can you provide specific examples of how this disparity manifests in policy decisions, resource allocation, and governance?

A: The delimitation freeze distorts a state’s electoral weight relative to its population, skewing both political dynamics and policy decisions. Take Bihar, for instance. With the fourth-largest number of Lok Sabha seats, the state commands sustained political attention. However, the artificially deflated value of its voters weakens their individual influence within the state’s power structure.

As a result, Bihar often outranks other states with similar developmental challenges in securing central government focus. Yet, the suppressed voting value ensures that fund allocations—both in nature and per capita distribution—prioritize political clientelism over genuine development. These suboptimal allocations fuel corruption, misallocation, and systemic inefficiencies, ultimately delaying meaningful progress.

Q: What economic benefits do you foresee from redrawing state boundaries to ensure population parity? Would smaller, more uniformly sized states lead to greater economic efficiency and governance effectiveness?

A: The economic advantages of smaller states are undeniable. Data consistently shows that newly created states in India have outpaced their parent states in economic growth. Smaller, more evenly sized states offer several key benefits.

First, they create a level playing field in negotiations, both with each other and with the Centre, reducing the risk of long-term favoritism. Second, India lacks significant “second cities”—urban centers comparable in size and influence to state capitals. This capital-centric governance fuels economic disparities, as administrative attention rarely extends beyond the capital’s immediate orbit. Smaller states can correct this imbalance, mirroring Germany’s historical experience, where a network of smaller political units fostered more equitable regional development.

Moreover, a compact geography and greater cultural cohesion enable states to develop specialized industries, benefiting both the local and national economies. Specialization, strategic focus, and balanced growth define this approach—ensuring a more sustainable and prosperous economic future.

Q: Redrawing state boundaries is an immensely complex and politically sensitive issue. What key challenges—constitutional, administrative, and political—would need to be addressed to make such a reform a reality?

A: There is no substantial constitutional challenge at play. Fundamentally, we are advocating for a return to the original framework of Articles 81 and 82—expanding its scope to include states. At the time of its drafting, the Constitution embraced an asymmetric structure with Part A, Part B, and Part C states, which was later standardized. Over time, Parliament has assumed unilateral authority to create or dissolve states.

This book underscores the intrinsic link between state sizes and delimitation, making it evident that periodic delimitation must align with state reorganization. The hurdles here are not constitutional; rather, this proposal reinforces the Constitution’s foundational logic. The real opposition is political, as evidenced by the recent inflammatory rhetoric from Tamil Nadu’s chief minister. However, the political calculus favors this approach. Smaller states tend to serve the interests of electoral incumbents in various ways, raising the possibility that—even if driven by self-interest—leaders may still pursue a delimitation process consistent with the book’s arguments.

Q: How do you counter concerns that smaller states might weaken India’s national unity or create additional governance inefficiencies, particularly in terms of coordination and resource distribution?

A: This concern is entirely misplaced. Smaller states do not threaten political integration—they strengthen it.

First, the stark imbalance in state sizes across India fuels a sense of alienation, particularly in the south and east. B.R. Ambedkar warned of the “balkanization” of southern states, while northern states remain disproportionately large. Equalizing state sizes would ensure a more balanced federal structure, fostering a sense of parity and fairness.

Second, the rigid “one language, one state” policy has exacerbated linguistic insecurity and chauvinism, triggering unnecessary conflicts. Smaller states, by contrast, allow micro-identities to flourish within broader regional frameworks. This recognition cultivates security and belonging, defusing identitarian tensions.

Moreover, the deep cultural and linguistic differences between neighboring states today reinforce division and sharpen regional identities. Smaller states would soften these contrasts, making distinctions more subtle and reducing friction.

Finally, smaller states promote economic efficiency. They enhance specialization, equalize bargaining power, and eliminate structural inefficiencies. This creates a more dynamic and balanced economy, benefiting all—except, of course, those who have built their political careers by stoking linguistic and regional divides.

Q: Given the political implications of redistributing parliamentary seats, how can we ensure that delimitation is carried out in a manner that is fair, transparent, and free from political manipulation?

A: Had delimitation not been frozen, India would have had a fully functional Delimitation Commission—an independent body akin to the Election Commission—tasked with conducting this critical exercise. We argue that since delimitation and state reorganization are inherently linked, both processes should occur regularly to maintain a balanced allocation of seats. The same commission should oversee state reorganization to ensure consistency and fairness.

Expanding the Delimitation Commission’s mandate to include state reorganization would create a constitutionally sanctioned, impartial mechanism. This approach would significantly reduce the risk of gerrymandering or undue political interference, preserving the integrity of the electoral system.

Q: Looking ahead, what are the key policy steps needed to build momentum for this critical reform, and how do you envision a more equitable and efficient democratic structure for Bharat in the future?

A: The first step is to make people understand that the delimitation freeze and the current system serve no one’s interests. The debate is wrongly framed as a North vs. South conflict when, in reality, this divide is merely a symptom of a deeper structural flaw.

The only viable solution is to restore Bharat’s civilizational norm of smaller administrative units. This ensures that every vote carries equal weight and every state holds proportional influence. The macrostructure must align with the micro, and vice versa.

This is a national issue that demands serious debate among the country’s intellectuals and thought leaders. It is far too important to be left solely in the hands of politicians and jurists. The delimitation freeze and its extension stem from a failure of national discourse and a political class that prioritizes convenience over effectiveness.

India’s democratic framework belongs to its people—not to its politicians, judges, or commentators.