In the mid-18th century, Haider Ali seized control of the Kingdom of Mysore from the Wodeyars, launching a relentless campaign to expand his dominion and challenge British forces. Over two stormy decades, he consolidated power through aggression and calculated military manoeuvres. His son, Tipu Sultan, inherited this volatile legacy. For 16 chaotic years, Tipu ruled with ambition and intensity, only to meet his end at Srirangapatna in the climactic conclusion of the Fourth Anglo–Mysore War. In the aftermath, the British reinstated a minor Wodeyar heir, signalling the end of the Mysore Sultanate—its brief dynasty bracketed between Haider Ali’s audacious rise and Tipu Sultan’s dramatic fall.

Together, the father-son duo provoked widespread fear and animosity across southern India. They waged repeated wars against the Marathas and inflicted devastating campaigns on regions like Malabar and Coorg. Their rule not only marginalized the Mughal emperor in Delhi but also alienated fellow Muslim rulers. Both the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Nawab of Arcot, recognizing the shifting power dynamics, allied themselves with the British.

Contrary to popular nationalist narratives, the Mysore Sultans did not resist colonialism in principle. Instead, they courted French support, with Tipu even inviting Napoleon Bonaparte to invade India. Yet, while modern admirers often whitewash their violent legacy, contemporary accounts and historical records—in both Indian and foreign languages—document their brutalities in vivid detail.

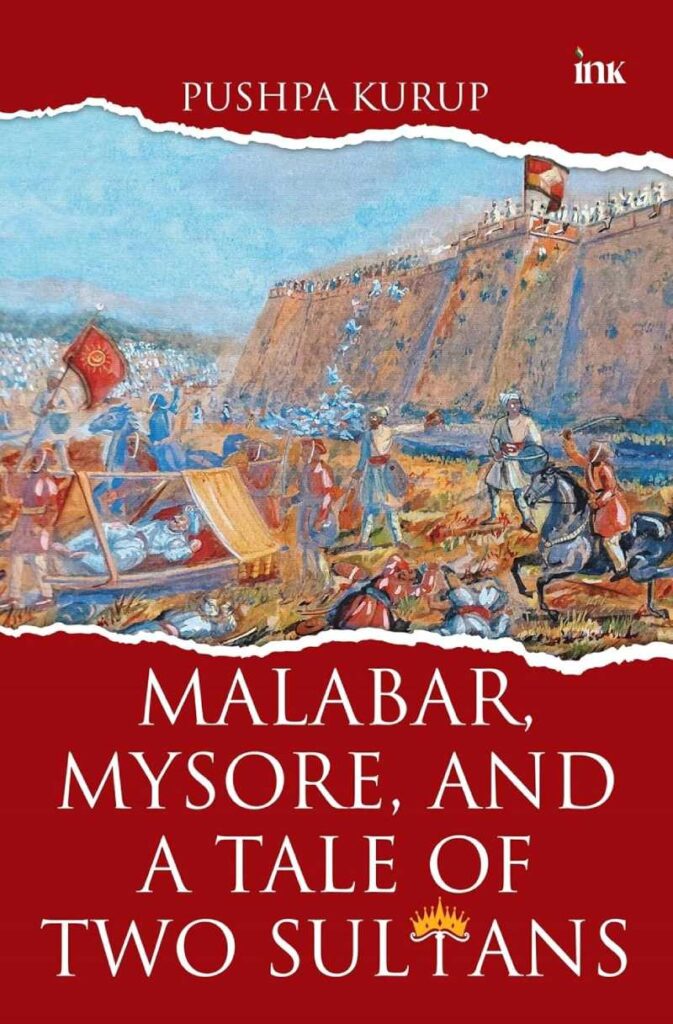

Pushpa Kurup’s book, Malabar, Mysore and A Tale of Two Sultans, published by Ink, cuts through myth and nostalgia to offer a nuanced examination of the Mysorean era. Drawing from archival sources and oral histories, she reconstructs the lived experiences of communities affected by Haider and Tipu’s campaigns.

In an exclusive conversation with The Interview World, Kurup shares the driving force behind her revisionist lens on Tipu Sultan’s rule. She delves into his geopolitical ambitions, challenges the prevailing glorification of his legacy, and positions her book as a critical intervention in the broader discourse on southern India’s history. Her insights offer a deeper understanding of the enduring socio-political consequences of the Mysore Sultanate. Here are the key takeaways from her illuminating conversation.

Q: Your book challenges the heroic narratives surrounding Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan. What motivated you to write a revisionist account of their reigns?

A: The legacy of the Mysore sultans—Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan—has long been defined by two competing narratives. One venerates them as enlightened rulers and formidable military tacticians who valiantly resisted British imperialism. The other sees them as ruthless usurpers—military autocrats who seized power, devastated neighboring kingdoms, and imposed a reign marked by forced conversions and religious persecution.

This book challenges both romanticized and vilifying portrayals, seeking instead to examine the historical record with impartial clarity. Through meticulous research, the heroic myth begins to erode, revealing uncomfortable truths. The sultans’ rule, far from idealized legend, was marred by coercion and violence.

Evidence clearly supports difficult conclusions. Temples were destroyed. Forced conversions occurred on a large scale. Velluva Kammaran Nambiar, for example, was renamed Ayaz Khan and appointed Governor of Bidanur under Haider Ali. British captives like John Scurry and John Bristow were forcibly circumcised and renamed. Tipu Sultan institutionalized such conversions, forming battalions of converted soldiers—Chelas, Ahmedies, and Usud Ilhyes.

Mass relocations, the desecration of churches and temples, and a systemic pattern of religious coercion characterized their rule. The historical record is unambiguous. It speaks not in whispers or conjecture, but with a stark, chilling certainty.

Q: Tipu Sultan is often portrayed as a martyr against British colonialism. How does your research complicate or contradict that perception?

A: Historical accounts challenge the popular image of Tipu Sultan as a martyr in the anti-colonial struggle. Contrary to romanticized portrayals, Tipu did not die heroically on an open battlefield. Instead, he was killed within the walls of the Srirangapatna fort in 1799 as British troops overran it. Though he died with a sword in hand, his end contrasts sharply with his earlier submission. In 1792, after the Third Anglo-Mysore War, Tipu signed a humiliating treaty, surrendering two of his sons as hostages and ceding vast territories—Malabar, Coorg, and more—alongside a heavy financial indemnity.

Why did he not choose to fight to the death then, when defeat had so deeply humiliated him? This question casts doubt on his valor, suggesting that his final stand may have been driven more by desperation than heroism. His military career, on close inspection, is marked more by setbacks than triumphs.

Tipu’s aspirations extended beyond political power. Like many rulers, he pursued conquest and wealth, but his campaigns often took on a communal character. He destroyed temples, imposed Islam on conquered populations, and, most notoriously, issued an extermination order against the Nairs of Malabar in 1788—an aborted act of mass violence.

By the late 18th century, power in southern India rested with the Marathas, the British, and Mysore. With Tipu’s fall, Britain’s ascendancy became absolute.

Q: The alliance with the French and the overture to Napoleon Bonaparte are especially intriguing. What does this reveal about Tipu’s larger geopolitical ambitions?

A: Tipu Sultan dedicated his life to resisting British dominance, while simultaneously seeking French support. Boldly ambitious, he courted an alliance with Napoleon Bonaparte and invited him to invade India, proposing that France and Mysore divide the subcontinent. To advance this vision, he sent envoys to the French governor of Mauritius, urging the dispatch of troops to expel the British. Governor Malartic responded enthusiastically, issuing a proclamation in January 1798, calling for volunteers to join Tipu’s cause. Once the British got wind of these developments, they swiftly resolved to neutralize him.

Tipu also employed religious diplomacy when it suited his goals. He reached out to the Sultan of Turkey and Zaman Shah of Afghanistan, invoking pan-Islamic unity. His appeal prompted Zaman Shah to invade India in 1797. Tipu’s ambitions didn’t stop there. He offered to lease Basra from the Ottoman Sultan in exchange for any Indian port of the Sultan’s choosing and even pledged to fund a canal linking the Euphrates to Najaf. Ultimately, his unrealistic schemes were dismissed, and his increasingly desperate manoeuvres only accelerated his political demise.

Q: Given the polarized views around Tipu Sultan—hero to some, tyrant to others—how do you hope this book will contribute to current public discourse on his legacy?

A: I hope this book plays a small but meaningful role in correcting the historical narrative. The towering image of Tipu Sultan didn’t arise naturally—it was carefully shaped, largely by British propaganda. Desperate to justify his elimination, the British orchestrated a relentless campaign to demonize him. They churned out volumes of letters, books, and paintings, crafting stories that cast him as a ruthless tyrant.

In response, Indian chroniclers may have overcompensated, romanticizing Tipu Sultan as a national hero. This reactive glorification pushed a vital figure into obscurity—Haider Ali. Few remember that it was Haider, not Tipu, who laid the foundation for Mysore’s rise. He seized power in 1761, when Tipu was just a child, and within two years had conquered the powerful Ikkeri kingdom. By 1766, Malabar had fallen to him. At his death, Haider Ali controlled much of southern India. Tipu, by contrast, lost those very territories, ending with his own fall.

Tipu’s legacy remains polarizing. But we must now engage with history honestly—not to stoke divisions, but to face difficult truths, and to hear the voices of communities still bearing the scars of the Mysorean campaigns.

Equally important is to remember those whose courage eclipsed even Tipu’s. In North Malabar, Pazhassi Raja resisted both Tipu and the British until his death in 1805. Puli Thevar, Veerapandiya Kattabomman, the Marudhu brothers, Gopala Nayak, Velu Thampi Dalawa, Kittur Rani Chennamma, Sangolli Rayanna, and Guddemane Appaiah—all stood tall against colonial oppression. Most paid with their lives.

These freedom fighters sought no fame—only liberation. It is time we etched their names into our collective conscience, where they rightly belong. Their sacrifices demand remembrance, and their stories must no longer linger in the shadows of history.

Q: If you had to summarize the lasting impact of Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan on the socio-political fabric of southern India, what would it be?

A: The Portuguese and Dutch ravaged India’s coasts with unchecked ambition. The British and French were no saints either. The Marathas played their part in the chaos. Yet, no force scarred the southern subcontinent as deeply—and as swiftly—as the Mysore sultans. In just four decades, their reign wrought destruction on a scale that eclipsed even the European colonizers.

Their campaigns devastated neighbouring economies and tore into the socio-political fabric of the region. They sowed communal discord, igniting Hindu-Muslim tensions that echoed through generations. Worst of all, their relentless warfare created the perfect opening for British imperial ambitions. Mercifully, their legacy left little of lasting substance. Though communal wounds lingered, time began to heal them. Tipu Sultan, in an effort to crush prosperity, ordered the uprooting of Malabar’s pepper vines. But nature and enterprise endured—the vines returned, and with them, the spice trade.

Tipu’s fall marked the end of Mysore’s imperial aspirations. The Wodeyars regained a diminished throne, while the Marathas, the Nizam, and the British divided the spoils. The British had already annexed Coorg and Malabar in 1792, after the Third Anglo-Mysore War. Cochin and Travancore soon became protectorates. Thus began nearly 150 years of British rule.

Today, Srirangapatna Fort stands in ruins—silent witness to a turbulent era. Tipu’s palace has vanished. Only the Daria Daulat Bagh, a few forts, mosques, and residences remain. For all their ambition, the Mysore sultans were not builders of enduring legacies. They left behind not monuments of glory, but the wreckage of a relentless will to dominate.