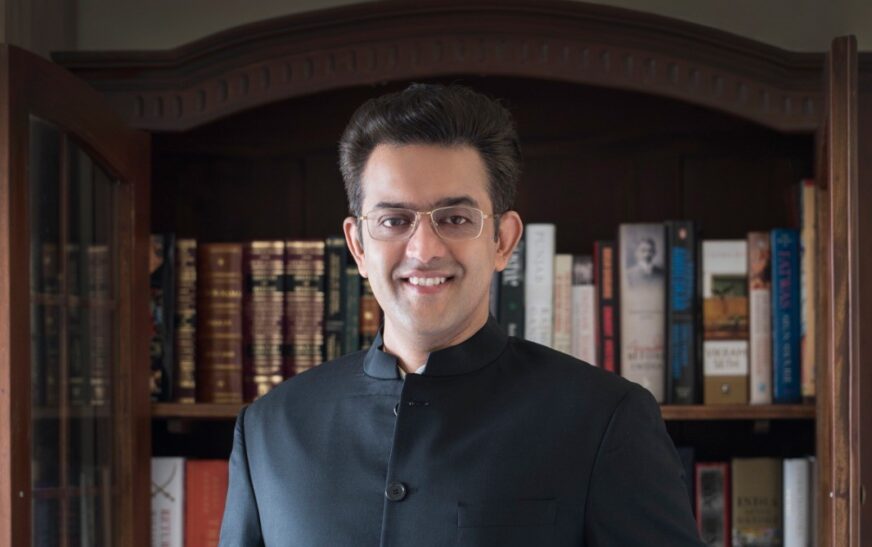

Historian Dr. Vikram Sampath, based in Bangalore, boasts an impressive portfolio of eight acclaimed books. Among them are titles like “Splendours of Royal Mysore: The Untold Story of the Wodeyars,” “Voice of the Veena: S. Balachander,” “Women of the Records and Indian Classical Music and the Gramophone, 1900–1930.” Noteworthy are his two-volume biography of V.D. Savarkar, titled “Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1881–1924” and “Savarkar: A Contested Legacy, 1924–1966,” along with his latest work, “Bravehearts of Bharat: Vignettes from Indian History,” which have all garnered national bestseller status.

In 2021, Vikram achieved the honor of being elected as a fellow of the esteemed Royal Historical Society. Furthermore, he received the Sahitya Akademi’s inaugural Yuva Puraskar in English literature and the ARSC International Award for excellence in historical research in New York for his book “My Name Is Gauhar Jaan: The Life and Times of a Musician,” which has since been adapted into the play “Gauhar” by Lillette Dubey. Adding to his accolades, Vikram was selected as one of four writers and artists for a writers-in-residence program at the Rashtrapati Bhawan in 2015.

With a doctorate in history and music from the University of Queensland, Australia, Vikram held the position of senior research fellow at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi, from 2017 to 2019. Additionally, he was affiliated with the Aspen Global Leadership Network and Eisenhower Fellowships in 2020 and served as a visiting fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin in 2010. Presently, he serves as an adjunct senior fellow at Monash University, Australia.

In a recent interview, Historian Dr. Vikram Sampath highlighted the incompleteness of the Somnath restoration project, stressing the necessity of restoring the Kashi Vishwanath Temple to its former glory. He emphasized the significance of Gyan Vapi as an integral part of the holy place associated with the ‘Shiva Jyotirlinga’.

During a conversation with Sandeep Joshi representing The Interview World, Dr. Vikram Sampath discussed his book “Waiting for Shiva: Unearthing the Truth of Kashi’s Gyan Vapi.” The book delves into the history, antiquity, and sanctity of Kashi as the abode of Bhagwan Shiva in the form of Vishweshwara, or Vishwanath. Here are the key insights from his interview.

Q: What are the reasons behind advocating for the full transfer of ownership of Gyan Vapi Mosque’s land to the Kashi Vishwanath Temple?

A: In the book, “Waiting for Shiva: Unearthing the Truth of Kashi’s Gyanvapi,” I’ve referenced court proceedings from a 1936 case filed by Din Mohammed and others against the Government of India. This case highlights a significant conclusion: the Gyan Vapi Mosque was deemed illegal according to Islamic jurisprudence, despite being an integral part of Hindu religious customs for centuries.

Moreover, the court’s decision was reinforced by the Allahabad High Court in 1942. Their ruling emphasized that the presence of temple ruins indicated the site’s previous Hindu ownership. According to strict Islamic laws, the mosque’s construction and use were deemed illegitimate because the consent of the Hindus wasn’t obtained for either building the mosque or praying at the site that rightfully belonged to them.

Q: What was the significance of the court case in establishing the existence of the temple predating the alleged demolition by Aurangzeb?

A: In 1991, Hindu activists in Varanasi initiated a civil case. Initially, the local court permitted limited prayers at the disputed site. During the hearing of the Din Mohammed versus Govt. of India case in 1936, Civil Judge S. B. Singh and Krishna Chandra referred to E. B. Havell’s book, “Benares: The Sacred City” (1905). Havell mentioned, “…at the back of the mosque of Aurangzeb (Gyan Vapi Mosque), near the Golden Temple (Vishwanath), is a fragment of what must have been a very imposing Brahmanical or Jain temple.”

In the Din Mohammed case, Muslim representatives acknowledged the demolition of hundreds of Hindu temples in Varanasi by Muslim rulers. This began with Qutb-ud-din Aibak and continued through Aurangzeb’s reign. The submission by then Secretary of State for India in Council, R. V. Vernede, argued that “the idols and the temple, which stand there (Gyan Vapi), existed long before the Islamic rule in India.”

The judge’s 1937 court ruling stated, “…the compound in which the mosque stands is that of the Gyan Vapi. In this compound, to the south of this mosque, there still exists that well, which is worshipped by Hindus as the primaeval source of knowledge…there is no reason to doubt that the mythological well is the same, which is to the south of the mosque in this very compound.”

Q: What were the diverse efforts across the nation aimed at protecting and revitalizing the Kashi Vishwanath Temple, as discussed in your book?

A: Ahilya Bai, the visionary ruler of Indore, galvanized a nationwide effort to rejuvenate and reclaim the essence of Kashi’s rich heritage. Leading the charge, she orchestrated the meticulous restoration of the revered Kashi Vishwanath Temple. Maharaja Ranjeet Singh of Punjab, along with other influential figures, rallied behind her cause, fortifying the collective endeavor. Their collaborative efforts symbolized a unified commitment to preserving and honoring the cultural legacy of Kashi, echoing across the diverse corners of the nation.

Q: What aspects contribute to the perception that Vallabhbhai Patel’s vision for the restoration of Jyotirlinga is incomplete?

A: Sardar Patel’s vision for the restoration of Hindu temples, which endured centuries of destruction under Muslim rulers, garnered the endorsement of Mahatma Gandhi. In a poignant speech delivered at Banaras Hindu University in 1916, Gandhi expressed profound dismay at the dismal condition of the Kashi Vishwanath Temple’s cramped and squalid passageways. He wholeheartedly supported the idea of resurrecting other important jyotirlingas as well. However, Gandhi advocated for financing through public contributions, emphasizing the need for communal involvement in preserving cultural heritage, rather than relying solely on government resources. This stance underscored Gandhi’s commitment to grassroots empowerment and communal responsibility.

Q: What historical and cultural factors have fueled the centuries-long struggle of Hindus for the preservation and restoration of the temple in Kashi, as referenced in your book?

A: The Hindu-Muslim riots of 1809-10, known as the ‘Lat Bhairo Riots’, were a testament to the intense struggle of Hindus to reclaim the sacred Kashi temple. ‘The Benares Gazetteer’ chronicled the two-year-long turmoil, emphasizing the underlying cause: the mosque erected by Aurangzeb on the revered site of the ancient Bisheshwar temple—a poignant symbol of historical significance. This mosque became the focal point of contention, igniting tensions that engulfed the city. The riots underscored the deep-rooted sentiments and the fervent desire of Hindus to preserve their cultural heritage, marking a pivotal chapter in the annals of religious conflict in India.

Q: What specific amendments do you propose for the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, and what are the reasons behind your recommendations?

A: The Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, demands reconsideration in light of recent archaeological findings at the Gyan Vapi Mosque, per court order. Enacted amidst the fervor of the Ramjanmabhoomi movement led by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and the Babri Mosque controversy, this law severely constrains Hindus’ ability to reclaim their sacred sites nationwide. Its stringent provisions impede the peaceful and legal pursuit of what rightfully belongs to them.

This legislation, by its very nature, restricts the fundamental rights of Hindus to worship freely and to seek redress for historical injustices. In questioning its validity, one must ponder the essence of justice in a democracy. Should a nation that upholds the rule of law allow such hindrances to the pursuit of justice and religious freedom? It is a paradox that begs examination and rectification. Revoking this act would signal a commitment to fairness, equality, and the protection of religious rights in a diverse and pluralistic society.